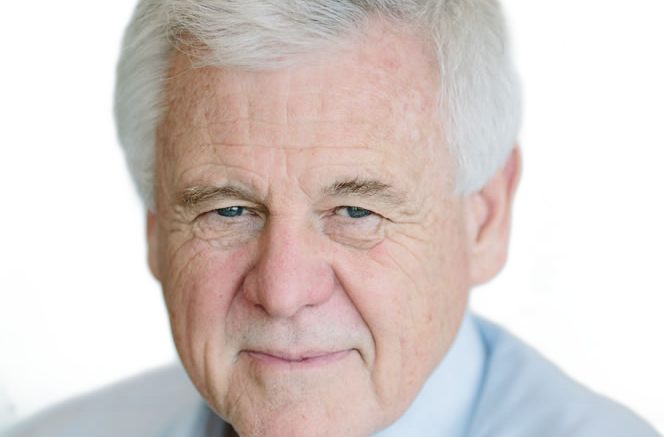

Professor Michael Thick, the chief medical officer and chief clinical information officer at IMS MAXIMS, finds a lot to welcome in the NHS’ latest ten-year plan; not least its conversion to a model of patient owned and accessible records that the company was exploring almost a decade ago.

Reading the NHS Long Term Plan, I had a definite sense of déjà vu. And that’s not just because we have seen similar plans in the past.

We have, of course, but this plan is still of interest and welcome. I think everybody would be very surprised if it were to last ten-years, but it’s good to have a clearly articulated vision for the service and where the technology should go.

The déjà vu arose from the plan’s commitment to integrated care services and, linked to that, its commitment to develop integrated care or personal health records to which people can contribute their own data.

Back in 2012, IMS MAXIMS did some work on a very similar concept. In the da Vinci project, we explored the idea of records that would be held remotely from hospitals and other providers, owned by patients, and accessed through smartphones and tablets.

It’s almost as if we had some kind of premonition that unless we give patients confidence in and control of their data, the changes we all want to see would not happen.

ICSs and PHRs: missing details and success factors

There is a lot we don’t know about the NHS Long Term Plan. It may be 130 pages long, and it may say that “by April 2021 we want ICSs covering all of the country”, but it doesn’t layout a blueprint for what an ICS will look like.

At the moment, there are 44 sustainability and transformation partnership areas, 14 of which are “working towards” ICS status. But our understanding is that the numbers will be slimmed down, so the new structures start to look more like the old regional or strategic health authorities.

The NHS is vast and there is always a question about how you can organise it so that what is said at the top happens at the bottom. Andrew Lansley’s 2012 reforms of the health service did not work, while the old RHA model was more successful.

So, a return to something like that would not be a surprise and I would welcome it; but for the moment, we don’t have some key details about how the ICSs will be organised, or operate, or spend money.

Nor do we have some key details about those new integrated care / personal health records. The plan suggests that the NHS summary care record is going to be merged into a personal health record created at local health and care record exemplar level.

We can assume that this will become the most basic kind of integrated care record, to which care plans will be added. That would enable the deployment of machine learning, or AI, so NHS data could be used as an asset in a way that has not been done before.

The plan also talks about extracting data to support population health management, planning and research. Current technology will support that, but there will need to be an overarching architecture to support data sharing across the NHS.

We don’t yet know if that will be uniform, or if local areas will have the freedom to experiment. Making sure that systems also use open standards will also be critical.

As founder members of INTEROPen, and strong supporters of the Professional Records Standards Body, we are up for that; but there will need to be a strong national, local and contracting push to make sure it happens.

Technology agendas to complete

Will also need to complete some of the work that is already in hand. Making sure the new integrated care / personal health records can interoperate with GP and hospital systems will be key.

So, GPs will need to open-up their systems and we will need to complete digitisation of hospitals. The plan addresses this in its chapter on technology, where it talks about extending the global digital exemplar programme, accelerating the roll-out of electronic patient records, and making sure that all providers reach a “core level of digitisation” by 2024.

It’s good to see an extension of the GDE programme. We have seen the impact of GDE status at our partner, Taunton and Somerset NHS Foundation Trust, and an extension will make best use of the effort that has gone into the programme and transfer that to other organisations.

Again, though, we will need to tweak the programme to make sure that its extension to more fast followers and to other trusts is done in a way that means they can adopt systems that are based on open architectures and standards.

Patient ownership of and confidence in data is key

Going back to that sense of déjà vu. It would be easy to ask whether the NHS will be able to deliver on such a challenging IT agenda, this time, when it has struggled in the past. I think there are reasons for optimism.

People need to understand that the whole of the NHS Long Term Plan is based on technology. If the NHS wants it to succeed, it will have to make sure that technology is funded and that the right people are in place to make it happen.

The plan talks about putting a chief information officer or chief clinical information officer on every board, and that’s good to see, but how will we make sure they are properly qualified and have the expertise to make the decisions necessary?

We will also need to bring clinicians and other staff with us. These plans are always people plans. A successful IT implementation is always 80% about the people and 20% about the technology.

That brings me back to those integrated care record / personal health records. The new approach is an important shift in policy, because previous attempts to digitise the NHS have been very possessive of data.

What we learned from the National Programme for IT and the care.data programme is that this will not work, and that people will not sign up for it, but the da Vinci programme was flying in the face of that orthodoxy.

The idea that patients should have ownership and responsibility for their health records, and that they should grant clinicians access to their data, was just too different to what people thought would happen. Yet, half a long-term plan later, that is what has come to pass.