As winter pressures combined with Covid-19 create more stress for the NHS, hospitals could look at reducing exacerbating factors such as acute kidney injury, says Dr Mark Ratnarajah, managing director, UK, of digital health company C2-Ai.

Scanning the news for the latest Covid-19 figures or tier restrictions has become a regular occurrence, and while the rates of infection may be levelling off in some areas, they are still on the rise in other regions. The prospect of mass vaccinations is giving hope that the pandemic will abate in 2021, but more immediately the NHS needs plans in place now to ensure it copes through winter.

According to media reports several intensive care units (ICU) in the Midlands have been working at full stretch (21-27 November), with 70-80 per cent of critical care patients having Covid-19. And options for reducing the load by transferring some critical patients to neighbouring hospitals were described by one NHS manager as having “dried up”.

On a national level, NHS England statistics have shown that a third of regional health systems (STPs and ICSs) surveyed at the end of November saw rising Covid-19 admissions, and that two-thirds of these saw an increase in overall bed occupancy of Covid-19 patients. While deaths from coronavirus are not as high as the peak of the first wave of the pandemic, the combination of the virus and winter pressures creates more stress in the system.

Yet, it’s not just the number of patients to consider, but other factors that complicate the scenario: staff absences due to illness or self-isolation put an additional burden on hospital teams; and social distancing required on Covid-19 wards inevitably leads to a reduction in available beds. Naturally, when hospitals are nearing maximum bed capacity, the knock-on effect means limited options to move patients to other wards if needed, and longer ambulance handover times from paramedics to triaging staff.

Research from the University of Warwick, The Alan Turing Institute, University of Exeter and University College London, showed that during the first wave of the pandemic, nearly a third of hospitals in England reached maximum ventilator bed capacity, so it would be easier if trusts can now formulate strategies to avoid the same crunch points in advance of the second wave colliding with increasing winter issues. One way would be to take measures to reduce avoidable harm.

Reducing avoidable harm

NHS staff have done a wonderful job throughout this pandemic, showing their dedication and hard work at every turn, despite all the physically tough and emotionally exhausting challenges. Unfortunately, some patients contract conditions in hospital because their immune system is weakened and because, in an environment where there are many ill people, viral infections can proliferate.

One common condition is hospital-acquired kidney injury (AKI). A study by researchers at University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust, found that AKI was a significant factor for Covid-19 admissions to ICU and deaths. AKI was present in 31 per cent of Covid-19 hospital patients, and the condition was associated with 27 per cent of admissions to ICU. The findings also showed that more than twice the number of Covid-19 patients with AKI died, compared to those without it.

As AKI can commonly be acquired in hospital, it would be beneficial to both patients and hospitals if clinicians are able to consider the likelihood of anyone contracting the condition. For this, an individualised risk-assessment of a patient is needed, rather than a generalised catch-all approach.

Considering all possibilities

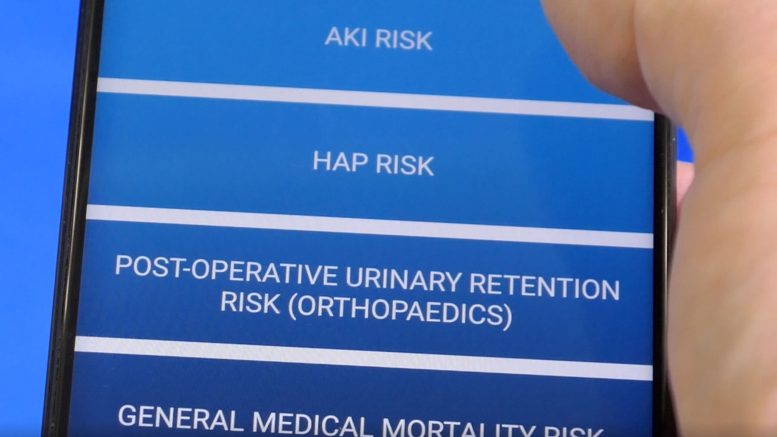

Some hospitals, both in the UK and other countries are now taking advantage of new technological systems that can carry out personalised risk assessments. This makes it easier for clinicians to look at many factors that might affect a patient’s health and how those conditions and circumstances can combine to indicate deterioration. Of course, if hospital staff can see what all the potential difficulties are, they can then take steps to put in place preventive measures and reduce harm. And not only can such technology assess a patient’s co-morbidities, but it can also give guidance on care. Based on data from healthcare organisations using this technology, it is anticipated that this preventative approach can reduce overall AKI levels by 50 per cent through significant reductions in hospital-acquired AKI and reduce hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) by a similar amount.

Much has been discussed during 2020 about the treatment of Covid-19 and of how the prevalence of cases has impacted NHS elective surgery. We must also consider how other conditions and circumstances complicate hospital care on a wider scale. Preventing conditions from developing will always be quicker than treatment and, naturally, will be better for the patient. On average, patients who contract AKI in hospital will require an extended stay of six days. And as we’ve seen, AKI has an increased risk of admittance to ICU.

If we give clinicians the technology to help prevent conditions such as AKI being contracted in hospital, we can see there would be decreased patient morbidity and mortality. This would also reduce pressure on staff, and in freeing up bed capacity – particularly in ICU – such measures would save trusts’ money. The reductions in these avoidable conditions could reduce direct costs to the NHS by £7m annually, save lives and also free up to 1,000 bed-days monthly (with up to 10 per cent of ICU capacity being freed). At a time when there is huge pressure on the NHS, surely empowering trusts with these tools has to be beneficial.