The MediShout App: Communication, Control and Capturing Staff Voice During Covid-19

Ashish Kalraiya1,4, Ben Walker2, Shiron Rajendran3, Sayinthen Vivekanantham1, Ian Gilmour1, Danny Sharpe1

1Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust

2University of Oxford

3University of Southampton

4NHS Innovation Accelerator

Keywords: Covid-19; logistical issues; mobile application; healthcare workers; National Health Service;

Abstract

Background

Covid-19 is exacerbating pre-existing pressures on healthcare systems. Frontline staff are relying more than usual on effective logistics and infrastructure to deliver patient care, for example provision of PPE, stock, facilities and equipment. Staff must adapt their ways of working in response to new challenges. Traditional communication channels within hospitals are often inefficient and not digitised, preventing healthcare organisations from adequately supporting staff and providing efficient solutions to problems.

Objectives

This study deployed the MediShout mobile phone application (app) to capture real-time data, on problems with logistics and infrastructure occurring in hospitals during the Covid-19 pandemic. The main objectives were to determine whether; healthcare staff would use the app, reporting led to immediate improvements, and data-collection could drive long-term transformational change and improve responses to future pandemics.

Methods

The app was used by staff to report issues with logistics and infrastructure across two hospital emergency departments (EDs) at Imperial College Healthcare Trust, UK. These reports were acted upon by senior physicians and nurses, operational managers and service helpdesks. Data was collected from the start of the first peak of Covid-19 in the UK, between March and April 2020. Data from each report were retrospectively analysed across multiple categories, including problem description and time of submission. To gauge the impact of each issue on clinical care, reports were scored against an impact scoring tool using a modified version of the World Health Organisation’s ‘quality of care’ definition.

Results

During this study, 94 reports were submitted. Reporting peaks were observed at times corresponding to clinical handovers. Peaks were also observed when changes had occurred to existing processes within the EDs. Impact analysis highlighted that every report sent had ‘impact’ or ‘significant impact’ on various aspects of care, including efficiency, patient safety and timely treatment.

Conclusions

The MediShout app captured valuable real-time data from frontline staff during the peak of Covid-19. Staff readily adopted the digital technology as it provided a more efficient way to resolve issues. This enabled hospitals to better allocate scarce resources, such as PPE, to those who needed it most. This study suggests listening to the voice of frontline staff during times of crisis allows more effective responses.

Capturing data during pandemics is critical for healthcare organisations to learn lessons and maintain control. During this study, it was established that most problems occurred due to changes in practice, such as dividing EDs into Covid-19 and non-Covid-19 zones, rather than increased caseload. Logistical and infrastructure issues were categorised as being ‘material’ (stock, equipment, medicines, or estates and facilities) or ‘workflow’ (task-management, new ways of working, infection control and communication) in nature. This provides healthcare organisations with a methodical tool for risk-assessing and coordinating future pandemic responses.

Background

Healthcare prior to Covid-19

The healthcare industry is perpetually under pressure to provide high quality, cost-effective, patient-centred care. The demand has gradually been rising over the years due to factors such as an ageing population,[1] the increasing prevalence of noncommunicable diseases [2,3] and the growing burden of largely preventable chronic conditions.[4] Even prior to Covid-19, logistical issues had a significant impact on clinical work with one report highlighting that approximately a third of NHS nurses waste more than one hour per shift finding missing equipment.[5]

Impact of Covid-19

The Covid-19 pandemic has exacerbated pressures already faced by healthcare systems. Globally, Covid-19 has forced healthcare organisations to enter crisis-mode making coordination of responses challenging. In the face of a disaster like Covid-19, frontline staff are even more reliant on well-functioning logistics and infra-structure to deliver care.[6] For example, staff require appropriate infection control measures such as clean working environments and personal protective equipment (PPE) to prevent spread of infection and save the lives of both patients and staff.[7]

The pandemic has forced healthcare organisations to rethink how healthcare is delivered with staff having to radically change their ways of working, often on an hourly basis. For example, elective work has been halted,[8] staff shift-patterns have changed and many clinicians have moved into sub-specialities they’ve not trained in.[9] Factors such as shortage of vital medical equipment, for example ventilators and PPE, are contributing to the psychological burden on healthcare workers.[10] Yet, job satisfaction of healthcare workers is critical for ensuring patients receive the best quality of care and ultimately feel satisfied.[11,12]

Digital Health

As healthcare systems adapt to new working conditions, Covid-19 has rapidly accelerated the need for digital health solutions and innovative technologies.[13] For example, GPs have radically changed their ways of working to adapt to the current crisis, resulting in demand for telemedicine soaring.[14] The importance of data, and not just patient data,[15] in the health and social care industry is becoming more apparent with global technology companies working with NHSx, the National Health Service’s digital branch, to help manage the coronavirus pandemic.[16]

However, many areas of healthcare still lack digital infrastructure and solutions to support frontline staff, who witness problems first-hand and in real-time. For example, most healthcare organisations lack efficient communication channels for staff to rapidly escalate logistical or infrastructure problems to the people or teams who create change. With healthcare staff relying on instant messaging mobile applications such as Whatsapp to communicate at work, the organisations that they work for are not able to respond rapidly or effectively to resolve issues.[17]

This lack of digital presence hugely impacts patient care. In the short-term, issues accumulate and delay staff, whilst in the long-term not collecting valuable data could prevent transformational change and better responses to future pandemics. Thus, whilst healthcare staff should be focused on treating patients, their time is often wasted by logistical and infrastructure issues such as insufficient PPE, estates and facilities problems, faulty IT or missing equipment, which they have difficulties reporting.[5]

MediShout is a mobile phone app that allows healthcare staff to instantly report any logistical or infrastructure problem they encounter to those who create change, such as senior physicians, senior nurses, operational managers and service helpdesk teams. By harnessing the insights of frontline staff, MediShout also hopes to better understand the challenges staff faced during the pandemic.

Objectives

This study aims to implement a mobile phone application (app) to capture real-time data on logistical and infrastructure problems occurring during Covid-19. The main objectives are:

- To determine if frontline healthcare staff would engage with digital technology during a pandemic, and use a mobile phone app to report logistical and infrastructure problems in real-time.

- To analyse the impact of problems reported and determine whether reporting led to immediate improvements in healthcare provision.

- To establish whether reported data can drive long-term transformational change and enable healthcare organisations to respond better to future crises, for example future surges of Covid-19 or new pandemics.

Methods

Data collection

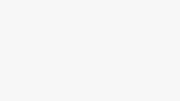

This study collected data using the MediShout mobile app,[18] which was made available to all staff working at the emergency departments (EDs) of Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust’s two main hospitals in London, United Kingdom. These hospitals were granted free unlimited use of MediShout, with their staff downloading the app and registering with a hospital email account. Staff could report any logistical or infrastructure issue relating to several broad categories; Covid-19, equipment, estates, facilities, stock or IT. The reports were accessed via the MediShout platform by senior members of the ED team; such as senior physicians, senior nurses and operational managers who would resolve issues themself or escalate issues to the relevant service helpdesk team (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The process of creating, resolving and downloading report data.

Data-Analysis

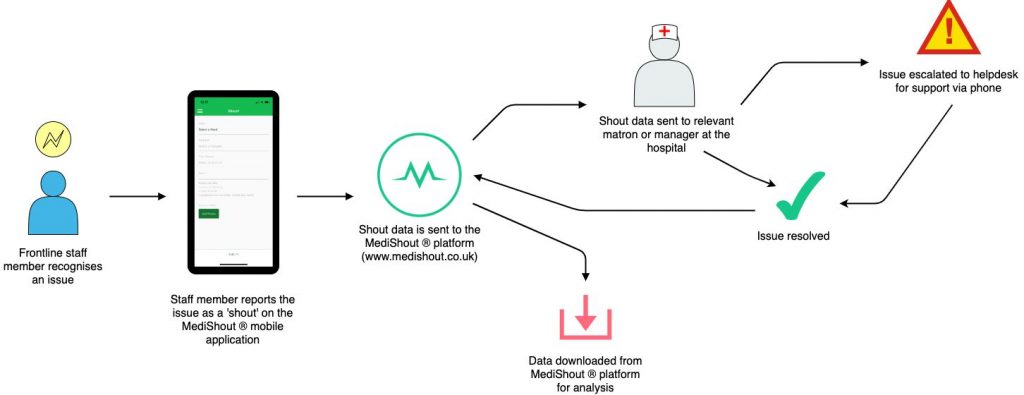

This study analysed data reported from the start of the first peak of Covid-19 in the UK in late March to early April 2020, and this time-period was chosen as it is when hospitals underwent major changes to their normal function. The data was cleaned with duplicate reports removed. A retrospective analysis was performed by comparing data collected within each report (Figure 2); including problem description, date and time stamp, issue-category, location, staff self-reported time wasted by issue and solution where available.

Figure 2. A mock-up view of the reporting interface for users.

Impact-Analysis

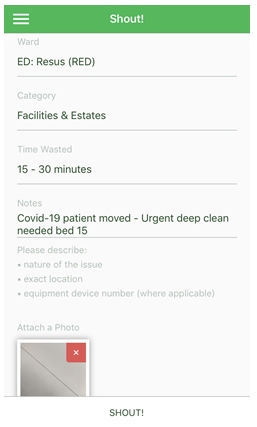

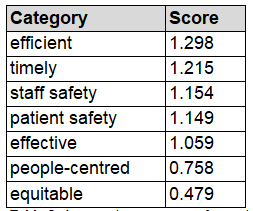

To gauge the impact of each issue reported, on clinical care, the authors created an impact scoring tool using a modified version of a World Health Organisation’s ‘quality of care’ definition [19]. This definition lists six criteria to determine ‘quality of care’, but for this study ‘safe’ was sub-categorised as ‘safe for patients’ and ‘safe for staff’ (Table 1).

Table 1. Categories of care quality, modified from the World Health Organisation.[19]

All reports sent via the MediShout app were assessed against each of these categories and scored as 0 (no impact on this category of care quality), 1 (impact on this category) or 2 (significant impact on this category). Therefore, each report had a maximum ‘impact score’ of 14. Four individuals scored the reports independently, and a mean score was calculated for each report.

Results

Data Collection

96 reports were sent from 23 unique users over the period of this study. The maximum number of reports submitted by a single user was 14.

Data-Analysis

Location:

44.1% of issues were reported from green (non Covid-19) areas, 41.9% from the red (Covid-19) areas and the remaining 14% from non-clinical areas such as offices or corridors.

Category:

48.4% of issues were categorised as Covid-19, 27.5% as facilities and estates, 16.5% as equipment and 7.7% as stock.

Staff self-reported time wasted:

35.1% of issues didn’t waste staff time, 29.8% of issues wasted 0-15 minutes, 9.6% of issues wasted 15-30 minutes, 6.4% wasted 30-60 minutes and 19.1% wasted 60+ minutes.

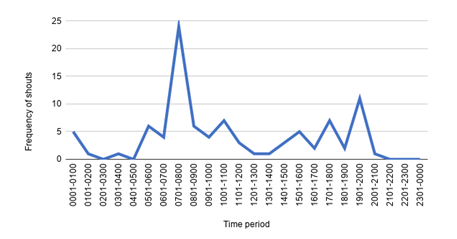

Time of shout:

Figure 3 shows a large peak of reporting between 07:01 and 08:00, and another smaller peak between 19:01 and 20:00. Reporting activity at these times were higher than the daily average.

Date of shout:

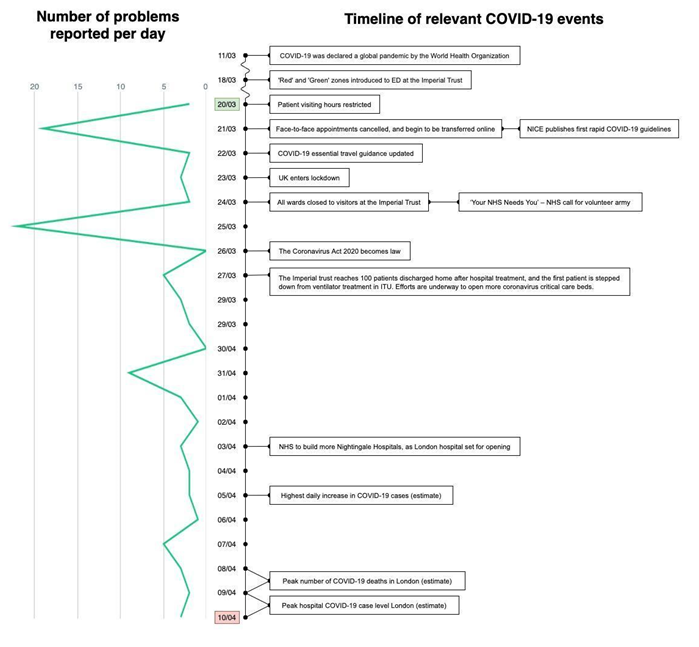

The distribution of shouts by date shows three noticeable peaks; March 21, 25 and 31.

Figure 3. Distribution of all shouts per hour, over 24 hours.

Impact analysis

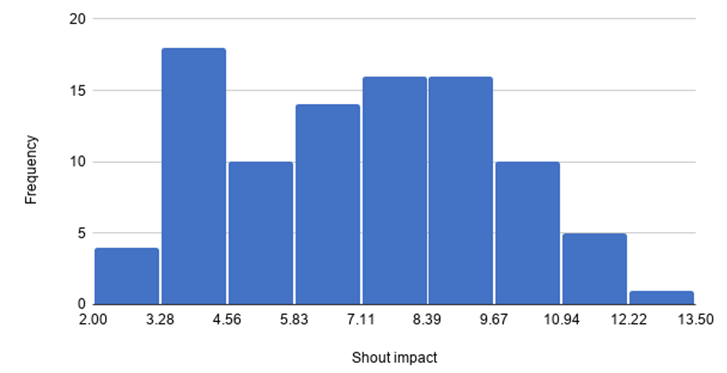

‘Efficient care’ was the aspect of care quality most impacted by the reported issues, with the highest average score of 1.298 out of a maximum of 2 (Table 2). The highest impact score for a report was 13.25, and the lowest was 2.25. The mean score was 7.111 and the median was 7.25. A full frequency distribution of the report impact scores can be seen in Figure 4, and a score for each report is available in Supplementary Figure 1.

Table 2. Average impact scores for each quality of care category. The categories are ranked by their scores.

Figure 4. A frequency distribution (histogram) of the report impact scores.

Analysis showed that reports with the highest impact score would often describe multiple issues within a single message. For example, the report that obtained the highest impact score of 13.25, described several issues such as ‘running low on Covid-19 swabs’, running ‘out/running low on blood cultures/Venturi mask/Venturi adapters’ whilst also highlighting issues about ‘capacity’.

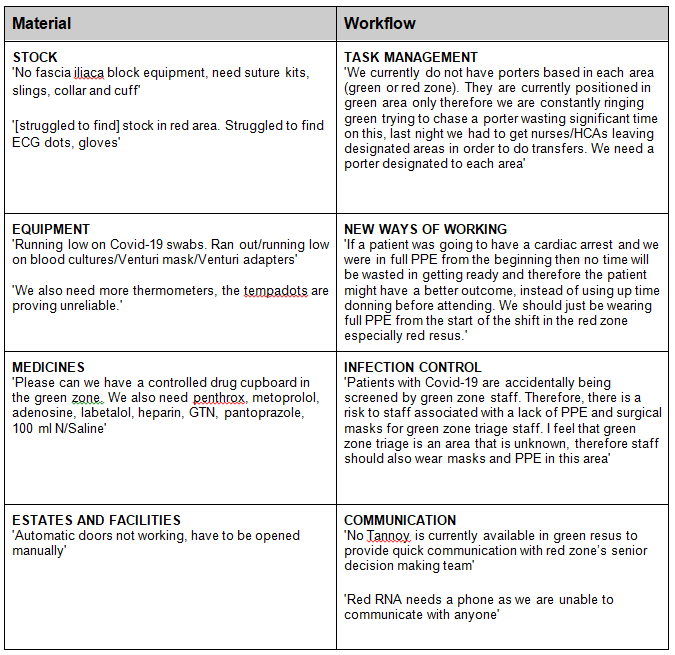

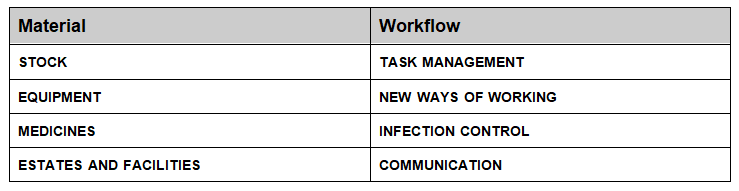

Themes also emerged during free-text analysis which enabled the authors to categorise all reports as being ‘material’ or ‘workflow’ in nature, as seen in Table 3. Material problems are issues with physical aspects of service provision and can be further sub-categorised as stock, equipment, medicines, or estates and facilities. Workflow problems relate to processes and can be further categorised as task-management, new ways of working, infection control and communication.

Table 3. Examples of problems reported, categorised into ‘material’ or ‘workflow’. Quotations have been taken directly from the data and only amended for the purpose of making grammatical sense.

Discussion

The first objective for this study was to assess the ability of the MediShout mobile phone app to be used by staff to capture real-time data on logistical and infrastructure problems. Around the peak of Covid-19 in the UK, 94 reports were sent using the MediShout app on a wide variety of issues. Staff voluntarily using this digital solution, without any form of direct incentivisation, highlights that they believe this form of communication could benefit their clinical practice.

A large peak of reporting was observed between 07:01 and 08:00, and another smaller peak at 19:01 to 20:00. Reporting activity at these times was higher than the daily average and coincided with the morning and evening handover meetings, where staff discuss both clinical and non-clinical issues. Without the app, staff would have to make time-consuming telephone calls or send emails, which could result in them missing vital parts of the hand-over, going home late or not reporting the issue.

Unreported and unresolved issues would have a huge knock-on effect for other staff, particularly when 65% of all reported problems wasted staff time. 20% of reported problems wasted an hour or more of staff time. The app provided staff with a quicker way of escalating any logistical or infra-structure problems encountered during their shift. This form of communication improved efficiency and saved time, highlighting why healthcare staff happily adopted the digital technology.

Figure 5. Timeline of COVID-19 related events highlighting that as more disruptions occurred in healthcare, more messages were sent using the mobile app. The first and last dates of data collection are shown in green and red respectively.

The second objective was to analyse the impact of reported problems and determine whether reporting led to immediate improvements in healthcare provision. The retrospective impact analysis demonstrated that the app enabled staff to highlight issues that were significantly impacting their ability to provide quality care. MediShout supported hospital teams and enabled them to resolve issues in a more efficient and effective way thus facilitating care improvements.

The majority of reported issues occurred in the two-week period after the healthcare system underwent major changes to its service provision, such as implementing red (Covid-19) areas, stopping elective care activities and requiring staff to wear PPE (Figure 5). The data collected from the app allowed hospital managers to respond rapidly to problems occurring on the frontline as a result of these changes.

By the third week of the study period, coinciding with the peak of the Covid-19 pandemic in London, far fewer reports were sent, indicating that the core issues had been resolved and the EDs were better prepared. By the time the peak caseload arrived, it seems staff were accustomed to the new ways of working and could focus on providing best care. The problems reported seem to be due to the changes in practice, and not related to the actual Covid-19 caseload itself. This implies that, if we can adequately accompany any changes to practice with staff feedback, healthcare environments will be able to respond to and manage crises more effectively.

The final objective was to establish whether reported data can drive long-term transformational change and enable healthcare organisations to respond better to future crises, for example another surge in Covid-19 cases. The data indicates that co-adaptation of frontline staff with their working environment, improves the capabilities of the healthcare system during a time of crisis. The valuable lessons from this study can be extrapolated and applied to other healthcare environments.

When times of crisis or pandemic occur, causing situations to evolve rapidly and change normal service provision, this study recommends that healthcare organisations adopt a methodical approach to managing logistical and infrastructure problems. Organisations should categorise all potential problems, risk-assess them and allocate managers to oversee problems deemed ‘high-impact’. A simple categorization system, based on the data analysed in the study, can be seen in Table 4.

Table 4. A way for healthcare organisations to categorise logistical and infra-structure problems occurring during a pandemic

This study also recommends that during pandemics, healthcare organisations should adopt digital technologies to engage their staff, act upon the problems they see in real-time and use the data to be better prepared next time. During this study, staff in non Covid-19 zones were not initially given PPE however those working in triage used MediShout to highlight the fact they were seeing Covid-19 patients (see Table 3). This consequently led to the hospitals updating their PPE policies, and the staff were appropriately given PPE for protection. Thus, listening to frontline staff enabled rapid responses and better allocation of scarce resources.

Limitations

The quantity and quality of reporting data is dependent on the information sent by staff using the mobile app. Thus, assumptions were made about the accuracy of the reported information. The app highlighted the unique experiences of staff and the problems that they encountered. However, the reported data also suggests that for optimal impact, the data should be considered alongside broader factors that contribute to best patient care. This will enable the full impact of each issue to be explored in more detail. The validity of the impact analysis tool was dependent on the strength of the WHO’s definitions, and the scoring system used to rate impact. Whilst the authors believe that the impact scale provided detailed metrics, this was performed retrospectively.

Future work

There are immediate opportunities for further research by collecting and analysing data from a larger pool of hospitals, and over a longer time frame. In addition, it would be insightful to prospectively understand the true impact of problems reported on wider healthcare systems. A larger quantity of follow-up data could be collected regarding reports and their resolutions, to identify more specific lessons for improving healthcare environments.

Conclusions

The use of the MediShout app in EDs captured valuable real-time data from frontline staff as they responded to the peak of Covid-19. This study indicates that listening to the voice of frontline staff during times of crisis enables healthcare organisations to respond to these challenges more effectively. Data collection is essential in ensuring better control, management and coordination of responses during pandemics and also normal times. The use of MediShout, and the categorisation of problems into material or workflow issues, provides healthcare organisations with a methodical tool for risk-assessing and coordinating future pandemic responses.

References

- Age UK. Briefing: Health and Care of Older People in England 2019. Available at: https://www.ageuk.org.uk/globalassets/age-uk/documents/reports-and-publications/reports-and-briefings/health–wellbeing/age_uk_briefing_state_of_health_and_care_of_older_people_july2019.pdf. Accessed May 20, 2020.

- Bertram M, Sweeny K, Lauer J, Chisholm D, Sheehan P, Rasmussen B et al. Investing in non-communicable diseases: an estimation of the return on investment for prevention and treatment services. The Lancet. 2018;391(10134):2071-2078.

- Atella V, Piano Mortari A, Kopinska J, Belotti F, Lapi F, Cricelli C et al. Trends in age-related disease burden and healthcare utilization. Aging Cell. 2018;18(1):e12861.

- Dixon-Fyle S, Kowallik T. Engaging consumers to manage health care demand [Internet]. McKinsey. Available at: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/engaging-consumers-to-manage-health-care-demand. Accessed May 20, 2020.

- Ford S. Nurses waste ‘an hour a shift’ finding equipment. Nurs Times. 2009;105(5):1.

- VanVactor J. Health care logistics: who has the ball during disaster?. Emerging Health Threats Journal. 2011;4(1):7167.

- Guidance for Health Workers. World Health Organisation. Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/health-workers. Accessed May 20, 2020.

- NHS operations cancelled for three months to free up hospital beds. The Independent. Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/health/coronavirus-uk-update-cases-nhs-beds-operations-latest-a9406966.html. Accessed May 19, 2020.

- COVID-19: FAQs about ethics. The British Medical Association. Available at: https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/covid-19/ethics/covid-19-faqs-about-ethics. Accessed May 20, 2020.

- Ayanian J. Mental Health Needs of Health Care Workers Providing Frontline COVID-19 Care. Jamanetwork.com. Available at: https://jamanetwork.com/channels/health-forum/fullarticle/2764228. Accessed May 18, 2020.

- Mosadeghrad A. Factors Influencing Healthcare Service Quality. International Journal of Health Policy and Management. 2014;3(2):77-89.

- Haas J, Cook E, Puopolo A, Burstin H, Cleary P, Brennan T. Is the professional satisfaction of general internists associated with patient satisfaction?. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2000;15(2):122-128.

- The impact of COVID-19 on health tech adoption in the UK. Healthcare IT News. Available at: https://www.healthcareitnews.com/news/europe/impact-covid-19-health-tech-adoption-uk. Accessed May 15, 2020.

- Browne R. Demand for telemedicine has exploded in the UK as doctors adapt to the coronavirus crisis. CNBC. Available at: https://www.cnbc.com/2020/04/09/telemedecine-demand-explodes-in-uk-as-gps-adapt-to-coronavirus-crisis.html. Accessed May 12, 2020.

- Manca DP. Do electronic medical records improve quality of care? Yes. Can Fam Physician. 2015;61(10):846‐851.

- Gould M, Joshi D, Tang M. The power of data in a pandemic – Technology in the NHS. Healthtech.blog.gov.uk. Available at: https://healthtech.blog.gov.uk/2020/03/28/the-power-of-data-in-a-pandemic/. Accessed May 18, 2020.

- WhatsApp. WhatsApp.com. Available at: https://www.whatsapp.com/. Accessed May 20, 2020.

- Medishout | We Shout, So Staff Don’t Have To. Medishout.co.uk. Available at: https://medishout.co.uk/. Accessed May 20, 2020.

- What is Quality of Care and why is it important?. World Health Organization. Available at: https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/quality-of-care/definition/en/. Accessed May 20, 2020.

Multimedia Appendix

Supplementary Figure 1. Average impact scores for each category of each shout, and their totals.

Abbreviations

PPE: Personal Protective Equipment

App: Mobile phone application

EDs: Emergency Departments